In The Art of Action, Stephen Bungay reveals that agility, empowerment, and decentralized decision-making aren’t as new as we think. These ideas have deep roots in military organizational theory, often predating modern management approaches by centuries.

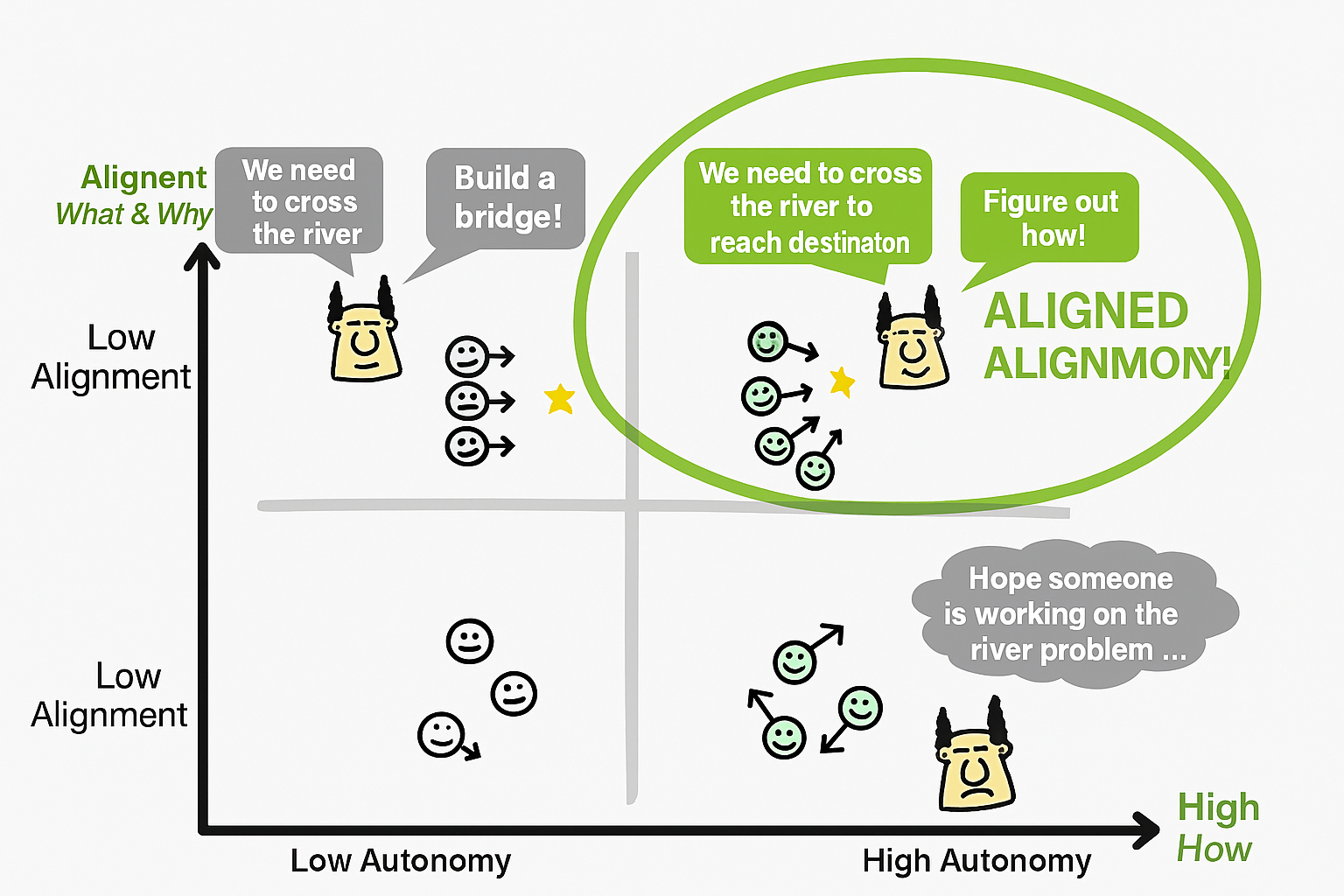

The core message of the book is that plans do not equal strategy, and acting under uncertainty requires both alignment and autonomy for the greatest chance of success.

Management theory feels cutting-edge, but military strategy has dealt with uncertainty and adaptive opponents far longer. Military history repeatedly shows the need to empower frontline units to adapt and make decisions on the spot, rather than waiting for central control.

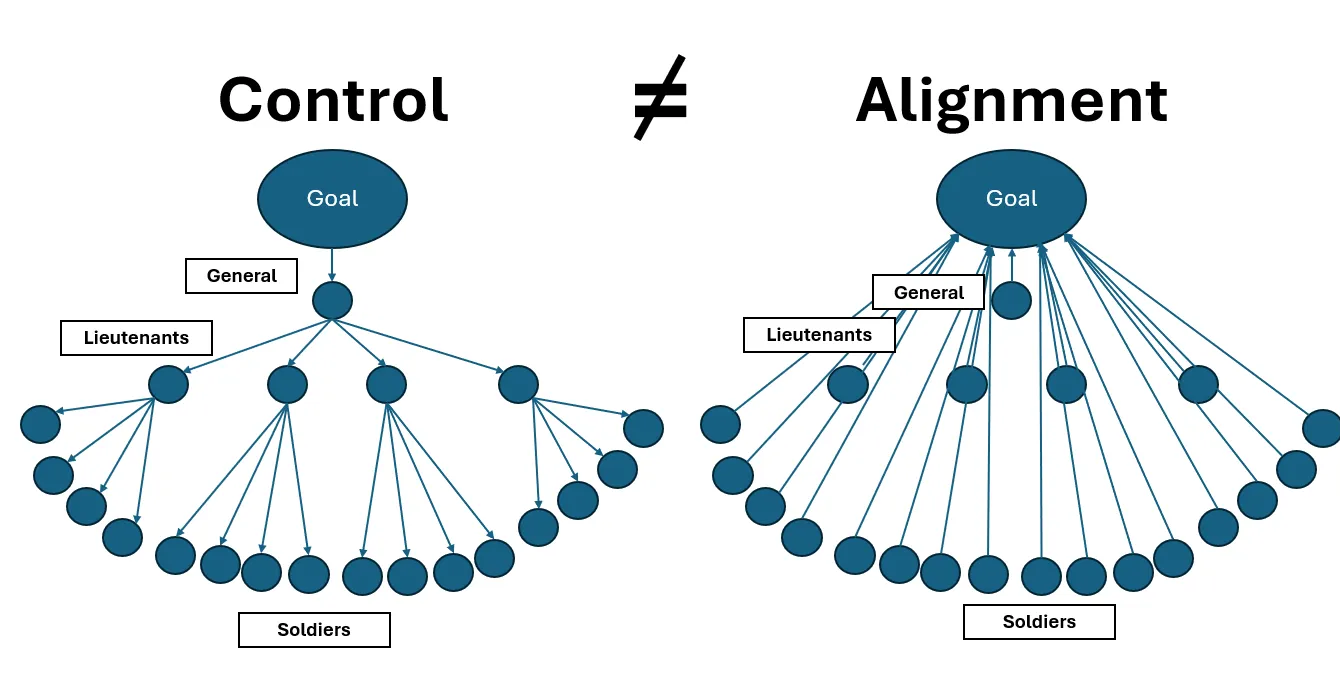

Organizations often confuse alignment with control, assuming tighter control equals better outcomes, especially under uncertainty. Military experience tells us otherwise: the real key is clear alignment around goals, not direct oversight.

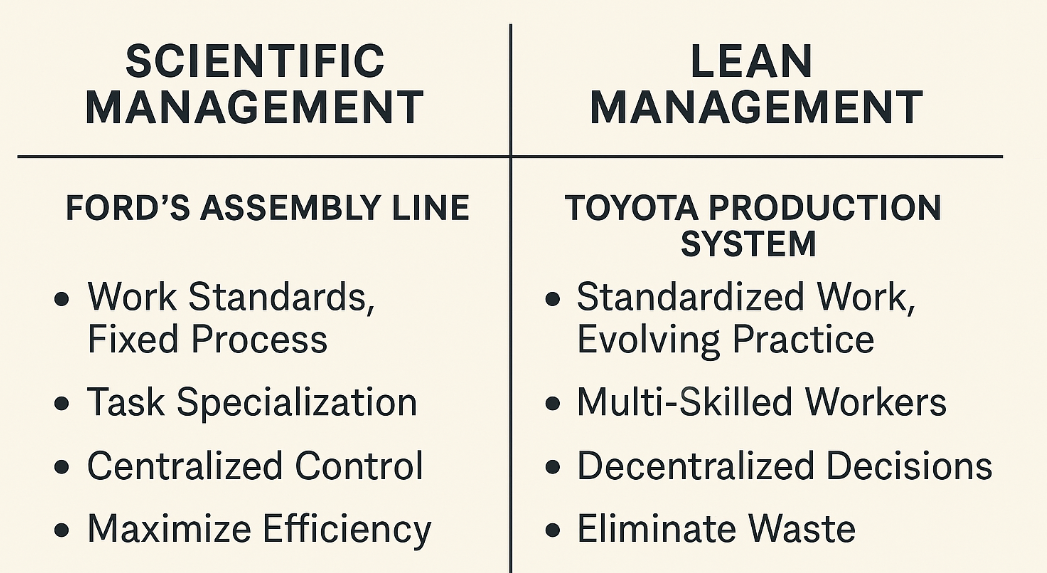

Consider the famous Ford versus Toyota example. Ford tightly controlled every task on the assembly line. Toyota, instead, aligned workers around standards and goals (like takt time and quality), giving them autonomy to adapt their work. The outcome was a flexible, responsive system—far more resilient than Ford’s tightly controlled method.

Another common mistake is believing alignment and autonomy are trade-offs. But real autonomy fits neatly into a tiered, goal-setting approach. Each level sets its own goals to support higher-level objectives, creating both alignment and autonomy simultaneously. Teams have the freedom to choose how best to achieve overarching goals.

This is exactly what the Objectives and Key Results (OKR) method—developed by Andy Grove at Intel and popularized by John Doerr—achieves. OKRs provide a means of describing the goal with an “objective” and then measuring it with key results (KRs), which are a key performance indicator with a target in time. The KRs can be measures of the objective itself or constraints for quality. Each level sets the direction for themselves and aligns to the higher level OKRs, and in doing so remain aligned and atleast semi-autonomous.

Yet OKRs aren’t entirely new either; they echo the German military doctrine of Auftragstaktik (Mission Command) from Helmuth von Moltke, where subordinates are empowered to act independently within commanders’ intentions.

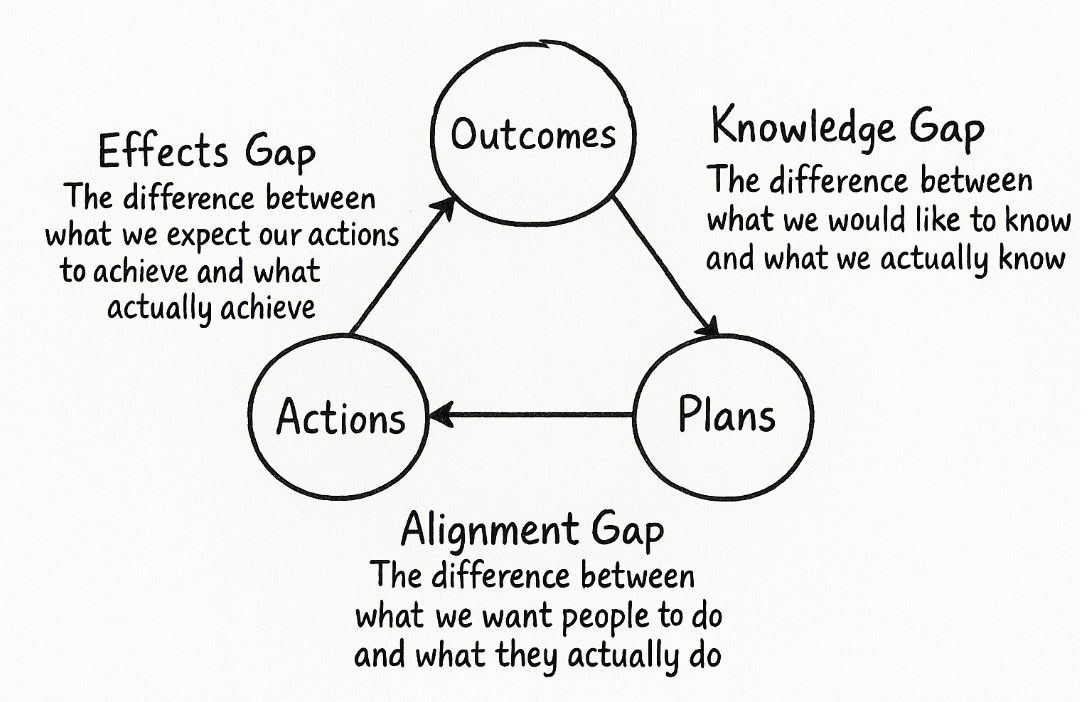

Recreated from Source: How Do We Get Speed, Innovation and Engagement? | by Erik Schön | An Idea (by Ingenious Piece) | Medium

Even Lean management principles have military origins. "Training Within Industry" (TWI), developed during WWII to improve manufacturing, laid the foundation for Lean Operations. These principles emphasize building team competence, solving problems locally, and allowing teams autonomy—exactly what modern Agile practices promote. And, of course, the rebuilding effort in Japan post-WWII was supported by the US government, with the lucky teaming of W. Edwards Demming and the Japanese Unions of Scientists and Engineers (JUSE).

Important note: One should not overlook the importance of Japanese culture in developing the Toyota Production System, with a sense of shared ownership, commitment to continuous improvement, and automation. These concepts were in Toyota’s DNA from long before it ever made a car. The first Jidoka (automation with human intelligence) was a self-powered and self-stopping loom in 1897 that detected and stopped making fabric if an error occurred (Toyota was originally a textile company).

Applying Lean principles to project management eventually led to Agile and reinvented product management. Jeff Sutherland brought in what he learned about leading under uncertainty in the Air Force as a Top Gun pilot and later about managing systems at scale (he has a PhD in biology). However, he used research from Bell Labs and the TPS way of management to design Scrum in the 90s, following many others influenced by the Lean Movement at that time.

Watch here one of my favorite clips on how Scrum evolved from research-based approaches under Jeff Sutherland and Ken Schwaber, as well as Toyota’s TPS: Scrum: The Structure of Scrum

Historically, product management was centralized at the senior executive or director level, tightly controlling "what" and "why" to build. Detailed planning, frequent data collection, and rigid control defined the role. However, true strategy is flexible, not a rigid plan.

This led us into what Melissa Perri describes as The Build Trap. We end up in a cycle of building more, committing to more, and driving harder to overcome gaps in our strategy assuming that it must just be a problem with execution. However, the gaps in strategy are naturally a result from attempts at detailed plans, controls, and the results of missed outcomes. Melissa borrows and attributes this insight to Stephen Bungay (Art of Action); and making a fantastic case for Product Management as a reinvented profession:

Recreated from Escaping the Build Trap: How Effective Product Management Creates Real Value (p. 69), by Melissa Perri

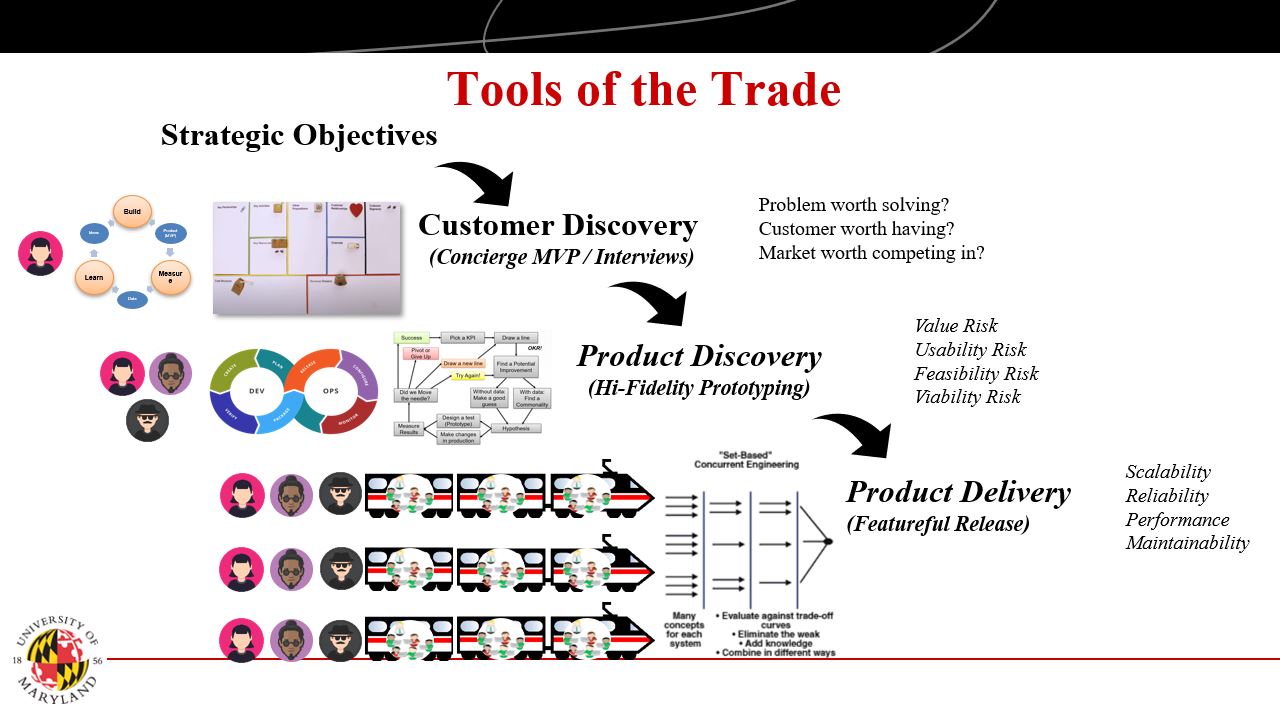

When an organization truly embraces autonomy and alignment, product management shifts dramatically. Product managers become embedded within agile teams, continuously sensing and responding to market needs, not just executing predetermined plans. And it requires empowering teams at all levels with product managers, some individual contributors on a team, to figure out the direction, the “what and why,” for the team.

Want to learn more? Check out this free mini-lesson on Modern Product Teams from the edX/MOOC Course “Modern Product Leadership:” Modern Product Teams, Lesson from Modern Product Leadership. (Available 7/3/2025 at 4PM EST)

Today’s leading organizations understand this deeply. Marty Cagan’s influential books (Inspired, Empowered, and Transformed) highlight the need for teams empowered with genuine product thinking and agile practices. Melissa Perri’s The Build Trap similarly emphasizes the importance of robust product management to avoid becoming mere feature factories and to develop a product function and career path within the organization. It’s the only way to effectively manage under uncertainty.

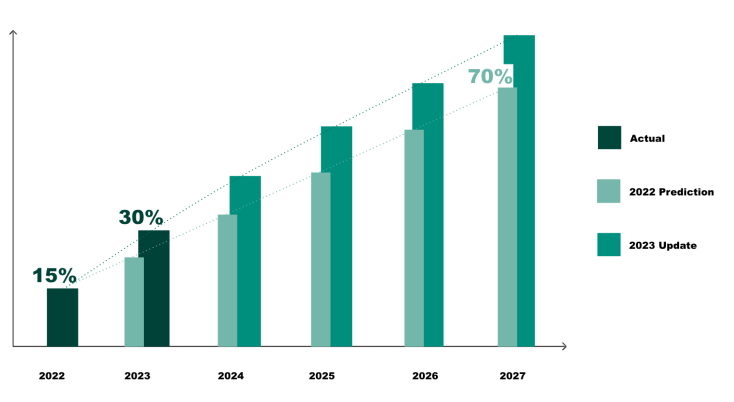

This explains why about 70% of companies are expected to have a Chief Product Officer (CPO) in their executive suite by 2027. Effective product management isn't just a process—it’s essential to true organizational agility and adaptability.

Percentage of Fortune 1000 Corporations with a CPO

Source: 2023 CPO Insights Report, 2023 CPO Insights Report: Presenting Original Research on the Chief Product Officer

Understanding this historical perspective helps organizations deeply align around goals while fostering real autonomy and innovation. Agility isn't a modern invention—it's a rediscovery of time-tested principles that drive resilience and adaptability in a constantly changing world.

If you liked this article, you might love our webinar series on the Product Operating Model. You can see the whole series here → Product@UMD Webinars

Want more great titles? check our Product Resources Page for recommended titles, in the "Books to Live By" section